Isaiah and the end of Babylon

On the evening of October 5, 539 BCE, the largest city of the time, Babylon, fell into the hands of the Medes and the Persians in an extraordinary way. On the one hand, their leader, Cyrus II, had the waters of the Euphrates River diverted from the city to reach it; then, his troops did not even have to fight to enter it since… the doors had been left open, the Babylonian ruler considering his city impregnable! But even more astonishing, these two so peculiar aspects of conquest had been clearly announced by the prophet Isaiah about… two centuries before! This can be hard to believe, let’s face it. Perhaps for this reason Isaiah was led to pronounce a second prophecy in connection with the fall of Babylon. Here is the statement:

« Babylon, the most marvelous city of any kingdom, the greatest pride of the Babylonian people, will be demolished by God like Sodom and Gomorrah. No one will ever live in Babylon again. It will be deserted »

Ésaïe 13:19-20, PDV

In your opinion, when did the « catastrophe » predicted here become apparent to everyone? This was not yet the case during the Persian intervention in 539 BCE, since the Nabonidus Chronicle states that after the capture of the city, « there was no interruption (of rites) of any kind in the Esagila or in any other temple and no (festival) date was missed » 1. In reality, « the conquest of Babylonia by Cyrus did not profoundly alter the socio-economic system in force at the time of the Chaldeans. The families of bankers-businessmen [continued] to prosper under the Achaemenides » 2. So, what had really changed? At most, the leader. Because « the administrative documents show us that, as a rule, the former officials were retained at their posts » 3, as was the case with the prophet Daniel. When nearly fifty thousand Jews were finally able to return to Jerusalem following a decree of Cyrus II (Ezra 2:64-65), their former capital was part of « a huge satrapy centered on Babylon, which was in fact the empire’s western capital, on a par with Susa, the central capital, and Ecbatana, the eastern capital » 4. How long would this situation of grace, far from being ‘catastrophic’, last?

Two decades had not passed since the Persian king Darius I, to establish his authority, had to overcome an unprecedented wave of rebellions, two of which occurred in Babylon. In a little over a year (October 522-November 521 BCE), two so-called « sons of Nabonidus » — Nidintu-Bel and Arakha — were called Nebuchadnezzar III and Nebuchadnezzar IV respectively to legitimize their accession to the throne. If the former was content with the title of « King of Babylon », the latter dared to usurp the very title of the Persian ruler, « King of Babylon and the Lands », who could not decently tolerate such an affront. Captured, the usurper and more than two thousand five hundred of his followers were cruelly executed. « Probably as a result of this political tension, local administrative functions, even at the lower levels, appear to have been transferred increasingly to [Persian] hands. Nevertheless Darius continued to hold court at Babylon (…) and to reside in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace (…). He also began the construction of a new palace and had the Euphrates diverted for this purpose. It was at Babylon that his son Xerxes gained experience in handling state affairs » 5. This undoubtedly helped the latter, in the second year of his reign, to overcome the nationalist pretensions of the usurpers Bel-Shimanni and Shamash-Eriba. The Persians only took three months to bring calm to Babylon, but this time, more than the inevitable execution of the rebels, it was the measures taken against the organization of the temples that were most sorely felt, as evidenced by the disappearance of many archives. « An almost unprecedented phenomenon in the history of Babylon », comments a reference book which further explains that « the end of the archives is largely confined to the north of Babylon, which had been the center of the rebellionshe end of archives is limited largely to northern Babylonia, which had been the center of the rebellions, and it affected mostly urban elite families who held priestly offices in the temples. The logical conclusion is that they must have been the main supporters of the uprisings and were brutally eliminated after the Persians regained control. (…) Babylon families were probably expelled from Uruk as part of the retributive measures enacted by Xerxes, whose aim may have been to dismantle the remnants of the former Babylonian state, its religious institutions, elites, and territorial cohesion » 6. Was this the beginning of the end announced for « the most marvelous city of any kingdom », as Isaiah described it?

Politically, Babylon was no longer and would never again be the power it once was. Economically, it suffered from a system of heavy taxation and its recent merger — as the ninth satrapy — with a very impoverished Assyria. However, its advantageous location in the heart of a warm and fertile region, enclosed between the Euphrates and the Tigris, guaranteed it a prosperous agriculture, notoriously linked to the intensive cultivation of date palms, the raw material of many craft activities. In fact, it is above all religiously that the Babylonians had to feel the most serious attacks, which an encyclopedia describes as: « A number of priests were executed. Esagila, the main temple, was badly damaged. Many objects from the temple’s treasury (…) were carried off to Persepolis (…). The gold statue of the god Marduk was also removed, so that nobody could now claim to be the rightful king, since, by Babylonian tradition, a new ruler was obliged to receive his authority from the hands of Marduk in the Esagila temple during the festival of the new year » 7. If the situation seemed ‘catastrophic’ to the Babylonians, the worst was yet to come!

While Alexander the Great intended to make Babylon the eastern capital of his empire, after his death one of his generals, Seleucus Nicator, resolved to build a rival city about sixty kilometres further north. Baptized Seleucia-on-the-Tiger — Babylon sitting on the Euphrates River — its construction was barely under way when Seleucus decided in 301 BCE, following the battle of Ipsus, to establish his new royal residence in Antioch, in northern Levantine Syria. However, this did not prevent him from encouraging the development of Seleucia… from the many Babylonian buildings in a state of disrepair! Perhaps it was to limit the degradation of the local heritage that a priest from Bel-Marduk named Berossus — Bel-re’ushunu in Babylonian — began to write in Greek a monumental history of the Mesopotamian civilization entitled Babyloniaka, that he dedicated to the son and successor of Seleucus, Antiochus I Soter, at his advent in 281 BCE. The goal sought does not seem to have been achieved, since his work had only a limited diffusion, fragments having only reached us through other authors such as Flavius Josephus. As for his beloved city, « a tablet dated 275 BCE states that on the 12th of Nisan the inhabitants of Babylon were transported to the new town (…). With this event the history of Babylon comes practically to an end, though more than a century later we find sacrifices performed in its old sanctuary » 8. Because the Seleucid rulers had « spared Babylon’s wall and the sanctuary of Bel, allowing the ‘Chaldeans’ to live around it » to perpetuate their « religious and cultural traditions », which explains the « statements by some Greek authors that Babylon had become inhabited mainly by priests » 9. « The greatest pride of the Babylonian people » — as Isaiah called it — was still in place!

In order to promote the Greek culture in Mesopotamia, Antiochus IV undertook a policy of colonization of Babylon, which he endowed for this purpose with a gymnasium and a remarkable theatre which, strangely, was a third larger than that of Seleucia, which was, however, a capital. This building was, it is said, ransacked in 127 BCE by the Parthian governor, a certain Himeros who, abusing his authority in the absence of the kings Phraates II and Artabanus II, too busy defending their empire on the front at the cost of their lives, would have oppressed the cities of Babylonia — including Seleucia and Ctephon — pillaging them and killing their inhabitants. After constantly harassing the residents of Babylon itself, he also burned down, in addition to the theatre, the temple of Bel and destroyed large parts of the city. « Despite these events, the chronicles tell us that political activities continued to take place in Babylon (…), as attested by [a] text (…) dated between 6 January and 4 February 124 BCE (…) [who] informs us above all about the political organization of the Greek community which was not governed by the same authority as the Babylonian population and which formed a separate community in the city. (…) However, this does not prevent members of both communities from working and trading together, as many contracts attest. The study of these texts also shows us that on this date, the city of Babylon does not seem deserted or burned, but that on the contrary, all daily activities still have their place there. The abuses of the tyrant Himeros, who ceased to exist around 127 BCE, must not have been so great as the sources lead us to believe » 10, especially since these sources are exclusively Western. On the Babylonian side, the chronicles indicate only the raids committed in Babylonia by Hyspaosines of Characene, before and after the takeover of the old Mesopotamian capital by the Parthian general Timarchus. Nevertheless, this troubled period marked the spirits enough that Babylon was only described as a city in ruins and depopulated. Curiously, it was around this time that the following words of a prophecy attributed to Isaiah were written in the Hebrew language on a large scroll: « Babylon, the most glorious of kingdoms, the flower of Chaldean pride, will be devastated like Sodom and Gomorrah when God destroyed them » (NLT), « it will never be inhabited again, and no one will live in it for generations » (GW). Do we not find here proof of a prophecy written after the events it describes?

In fact, from the last century before the Christian era, « we do not possess a clear picture of the rate of Babylon’s decline in economic importance or its depopulation over the centuries » 11. If the testimony of Diodorus Siculus, around 30 BCE, still seems acceptable when he declares « today only a small part of Babylon is inhabited; the rest of the space within its walls is converted into cultivated fields » 12, we do not know what credit to give to Strabo when he reports that « Babylon, currently [under the reign of Caesar Augustus], is almost entirely deserted » 13. Has he ever visited it? Under Nero, Pliny the Elder writes that « Babylon (…) has become a desert » 14, yet it hosts a Christian congregation — from which the apostle Peter writes his first epistle (1 Peter 5:13) — which is close to temples from which still come documents in cuneiform script, the last being « an astronomical ‘almanac’ (…) written in A.D. 74-5 » 15. When Pausanias and Lucian of Samosata, in the second century, describe « the walls of Babylon », it seems obvious that they have never seen them, which the former explicitly recognizes in another place 16. Yet it was at the end of the same century that the theatre inaugurated by Antiochus IV was not only restored but even enlarged! Similarly, while Eusebius of Caesarea and Jerome of Stridon support the desertitude of Babylon in their commentaries on chapter 13 of the book of Isaiah, written respectively at the beginning and end of the fourth century, it is noted with interest that « a Church of Babylon (…) which the Jews destroyed during the persecution of Shapur [II] » is restored « in the year 399 of Christ » 17. The fact that Babylon was still inhabited in the fifth century emerges from these words of Theodoret: « Few people still inhabit it, and they are neither Assyrians nor Chaldeans but Jews » 18, Jews whose presence is well confirmed by two contemporary texts of the Talmud 19. In truth, the last attestation of the occupation of the site is that of the great traveller Mohammed Ibn Hauqal who reported again « a small village at Babel », the northern district of Babylon, in the middle of… the tenth century of our era!

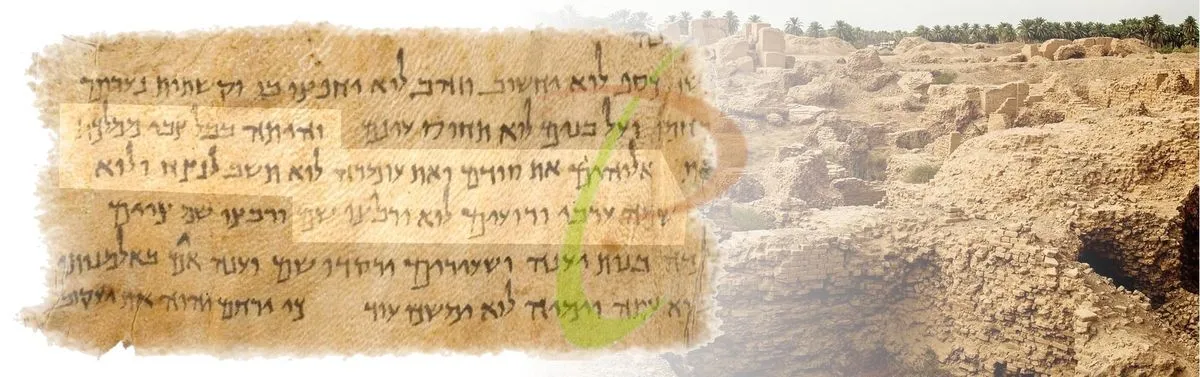

Thus, it seems certain that « the complete abandonment [of Babylon] was extremely long, probably in the order of 1,500 years » 20, and it was not apparent to everyone until a thousand years after the writing of this great scroll which we have mentioned above. Found in a Qumran cave in an excellent state of conservation, it is now on display at the Jerusalem Museum, after being dated between 125 and 100 BCE. This scroll contains the whole book of Isaiah, including the prophecy contained in chapter 13, which was — and still is — being fulfilled. This means that it was impossible for any human being to predict accurately, not only the terrible agony that would befall Babylon, but even more the interminable period of desolation that it would endure until our days, it which was, « in Nebuchadnezzar’s day », the largest city in the world, with a « population (…) estimated at about a half million » individuals 21. The fate of Babylon bears witness that the only person who could both proclaim centuries in advance, and keep a watchful eye on the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophetic declarations, can only be the God of the prophet — Jehovah, the very Author of the Bible!

References

| 1 | Jean-Jacques Glassner, « Mesopotamian Chronicles », 2004, pp. 237, 239. |

| 2 |

Georges Roux, « La Mésopotamie », 1985, p. 340. |

| 3 |

Albert T. Olmstead, « History of the Persian Empire », 1948, p. 51. |

| 4,5 |

Guillaume Cardascia, « Babylon », Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 3, 1988, pp. 325-326. |

| 6 |

Paul-Alain Beaulieu, « A History of Babylon, 2200 BC-AD 75 », 2018, p. 254. |

| 7 |

Muhammad A. Dandamayev, « History of Babylonia in the Median and Achaemenid periods », Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 3, 1988, pp. 326-334. |

| 8 |

Archibald Henry Sayce, « Encyclopedia Britannica », Vol. 3, 1911, p. 98. |

| 9 |

Paul-Alain Beaulieu, « A History of Babylon, 2200 BC-AD 75 », 2018, pp. 260-261. |

| 10 |

Patrick Michel, « Le théâtre de Babylone: nouveauté urbaine et néologisme en Mésopotamie », Études de lettres, 1-2, 2011, pp. 153-170 §§ 12, 17, 24-25. |

| 11 |

Michael Ferguson, « Babylon: Legend, History and the Ancient City », 2014, p. 44. |

| 12 |

Diodore de Sicile, « Bibliotheca historica », II, 9. |

| 13 | Strabon, « Geographica », XVI, 5. |

| 14 |

Pline l’Ancien, « Naturalis Historia », VI, 30. |

| 15 |

Georges Roux, « La Mésopotamie », 1985, p. 352; « Ancient Iraq », 1993, p. 420. |

| 16 | Pausanias, « Messenia », XXXI, 5; « Arcadia », XXXIII, 3. |

| 17 |

Jules-Simon Assemani, « Bibliotheca Orientalis Clementino-Vaticana », Vol. 3-2, II, 1728, p. 61. |

| 18 |

Théodoret, « In Isaiam », V, 158-159. |

| 19 |

Talmud de Babylone, Gittin 65a; Baba Batra 22a. |

| 20 |

Michael Ferguson, « Babylon: Legend, History and the Ancient City », 2014, p. 44. |

| 21 |

Merrill Unger, « Babylon », The New Unger’s Bible Dictionary, 1988, p. 191. |