The Moabite Stone

On August 19, 1868, Frederick Augustus Klein, an Anglican priest from Prussia, discovered intact among the ruins of the ancient Dibôn (now Dhibân in Jordan), north of the Arnon Valley, a large stele in black basalt containing inscriptions in the Phoenician linear alphabet. The announcement of this discovery aroused a veritable effervescence among archaeologists, as did the anger of the local Bedouins who, in a gesture of defiance towards the Ottoman authority, broke the stele in November 1869. His registration could have been lost forever!

However, Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, then an official at the French Consulate in Jerusalem, had managed to obtain a stamping the previous month. When two of the largest fragments of the stele were found in mid-January 1870, he acquired it, followed by that of many other smaller fragments which he donated in 1873 to the Musée du Louvre in Paris, which continued to collect pieces… until 1891! A long and meticulous work of reconstitution was then undertaken « by means of the original fragments and the plaster restorations which were carried out thanks to the stamping of the Moabite stone » 1.

What testimony offers us today this block of stone so patiently restored? First, it indirectly confirms the accuracy of several passages of the Holy Scriptures. Thus the inscription which is engraved on the Moabite stone is one of the few documents which one possesses in the Moabite language, considered as a dialect close to the biblical Hebrew, which is supported by Genesis 19:36-37 which traces the origin of the Moabites back to the days of Lot, the nephew of Abraham the Hebrew. Moreover, the dedication of the stele to the god Kemosh attests to the preponderance of his worship among the Moabites, called « the people of Kemosh » in Numbers 21:29. Likewise, it confirms the historicity of king Mesha and his revolt against the successors of king Omri of Israel, which is reported in 2 Kings 3:4-27. In the statement of his alleged victory over the enemy armies, the Moabite king declared that he had taken back to the Israelites and fortified Ataroth, Jahaz and Nebo. Concerning the first city, Mesha says in lines 10 and 11 of the inscription: « The people of Gad had always inhabited the land of Ataroth, and the king of Israel had built Ataroth there. I fought against the city and took it. And I killed all the people of the city to satisfy Kemosh and Moab » 2. This establishes a direct link with the text of Numbers 32:34-37 which reports: « Then the children of Gad built Dibón, Ataroth, Aroer (…) of the fortified cities; (…) And the children of Reuben built (…) Kiriataim, Nebo, Baal-Meon.» The mention of all these cities on the Moabite stone brings additional credit to the Bible, and in particular to the writings of Moses, editor of the Book of Numbers.

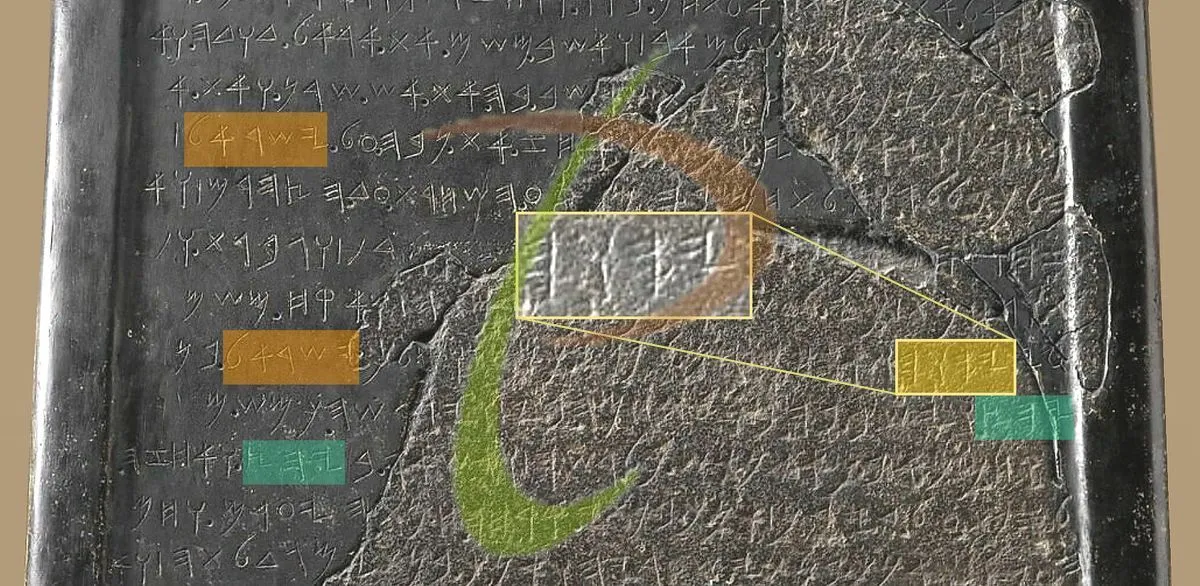

However even more remarkable is the mention by Mesha of the personal name of the God of Israel, in the form of the Tetragrammaton YHWH, at the beginning of the 18th line of his narrative (picture above). In this passage in which he speaks of the reconquest of Nebo, the Moabite king brags: « I took from thence the [vessels] of Yahweh, and brought them before Chemosh » 3. This statement is the oldest extra-biblical reference to the divine name discovered to this day. But it is also proof that the personal name of God, if it were not unknown to a foreigner — moreover, to a long-standing enemy — was obviously freely used by the Israelites themselves, as James King already confirmed, in the work he published on the Moabite stone, ten years after its discovery:

« It is well known that the sacred word Jehovah, the Tetragrammaton of the Greeks, was held so sacred by the Jews of later times, that it was never pronounced except by the High Priest, and that only once a year, on the day of atonement when he entered the most holy place; (…) It has always been a moot point how or when this pious horror of mentioning Jehovah’s name was introduced;(…) And it is evident from the Moabite stone, that even in the days of Mesha that august name of the true God was so commonly pronounced by the Hebrews as to be familiar to their heathen neighbours, and commonly regarded by them as the characteristic name of the God of Israel »

James KING 4

Thus, in dedicating a stele to his warrior-god Kemosh, Mesha also testified to a truth that is precious to us today: the prohibition of mentioning the divine name, which some linked to the third commandment that Moses recorded in Exodus 20:7, was totally unknown about 900 BCE, date of erection of the stele. What then must we conclude from this? That this practice, introduced late into Judaism, never had any scriptural foundation. Moreover, it does not justify in any way the withdrawal often observed in the Word of God of the personal name of His author — Yahweh or Jehovah! Finally, let nothing in truth keep us from making respectful use of it in our prayers!

References

| 1 | Henri Michaud, « Sur la pierre et l’argile », 1958, p. 35. |

| 2,3 | Ibid., pp. 37-38. |

| 3 | James King, « Moab’s Patriarchal Stone : being an account of the Moabite stone, its story and teaching », 1878, pp. 101-102. |