Belshazzar and Daniel

On the night of October 5-6, 539 BCE, Babylon, the largest city of the time, fell into the hands of the Medes and the Persians, conquered without any resistance. How could this have happened? Herodotus replied: « As it happened that it was a feast day for them, they danced during this time and indulged in pleasures, until the hour when they learned of the misfortune that had just happened » 1. Confirming that the Babylonians were busy entertaining themselves, Xenophon reported two additional details: « The doors [of Babylon were] open during that night when the whole city [was] rejoicing » and ‘arrived at the king’s side’, «soldiers from Gadatas and Gobryas [the generals of Cyrus II] laid hands on him [and killed him] with those around him » 2. If the two Greek authors thus support the biblical account of the book of Daniel, only the latter reveals the name of the monarch who tragically lost his life that evening: Belshazzar, sometimes also called Balthazar. As one of the three Magi of the Christian tradition! For a long time, their only common thread was that they never existed in the eyes of the Bible critics.

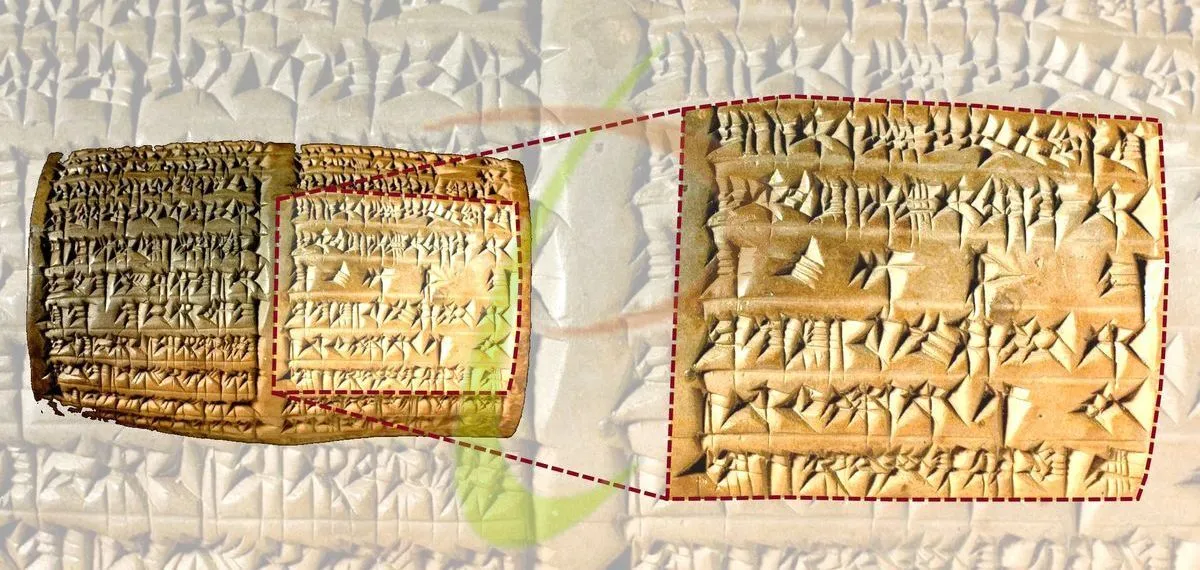

Until the middle of the 19th century, the Bible was the only work to mention the name of Belshazzar. Moreover, it even presented him as the last ruler of Babylon, in the place of her father Nabonidus — non-existent. These two reasons were sufficient for the critics to deny any historical value to the book of Daniel which, according to them, was only a propaganda document produced « during the time of the persecution of the Jews in Palestine by Antiochus IV » 3. The tide began to turn in 1854 when John E. Taylor, a British consul, discovered among the ruins of Ur’s ziggurat several clay cylinders, about ten centimeters long, which had inscriptions on two columns in cuneiform script. One of these inscriptions (BM 91128) contained a long prayer addressed to the moon-god Sin, which was translated for the first time by H. Fox Talbot in 1861 4. Here is a translation from lines 18 to 26 of the second column: « As for me, Nabonidus, king of Babylon, save me from sinning against your great divinity and grant me a long life [literally “a life of long days”]. Moreover, with regard to Belshazzar, my first-born son, my own offspring, have the fear of your great divinity placed in his heart so that he does not commit any sin. May he be sated with happiness in life » 5. From these few lines, it is clear that a Belshazzar — Bel-šar-usur on the inscription — was indeed linked to Nabonidus, the last official king of Babylon. But what was his exact position?

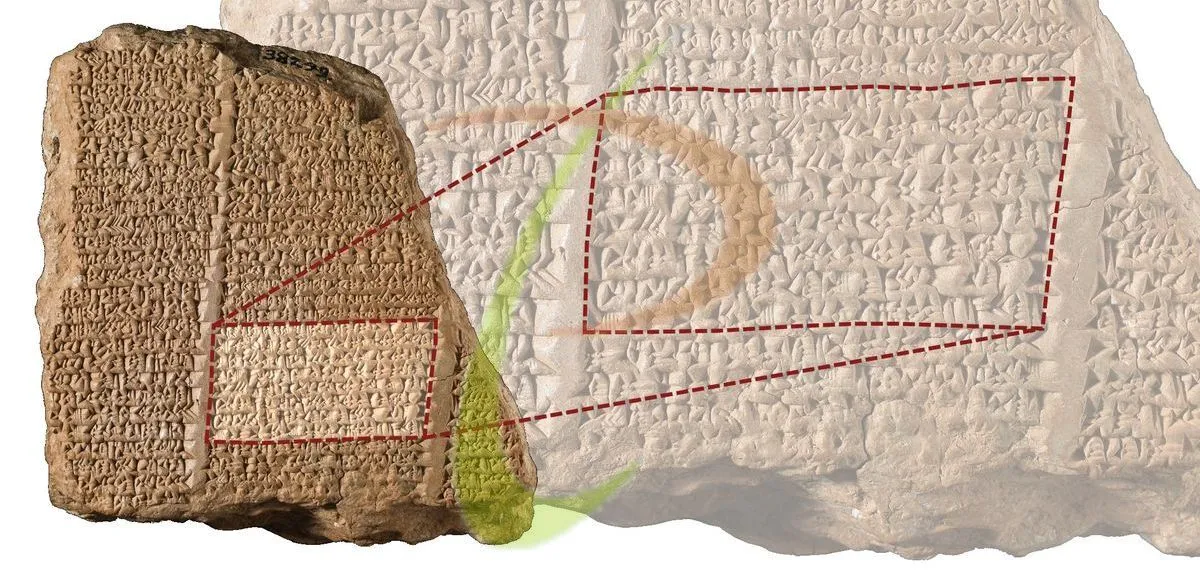

In 1882, Theophilus G. Pinches published a translation of an inscription now known as the Nabonidus Chronicle. Renowned for its description of the siege of Babylon by the armies of Cyrus II, it also reports that Nabonidus was absent from Babylon for many years. For example, « the seventh year: the king was in Tema while the prince, the officers, and his army were in Akkad [Babylonia]. The king did not come to Babylon » 6. This statement, with a few details, is repeated for the ninth, tenth and eleventh years of the reign of Nabonidus. In fact, it urged Pinches to conclude early that the « prince » Belshazzar seemed “to have been commander-in-chief of the army, perhaps had greater power in the kingdom than his father, and so was regarded as king » 7. However, it was not until 1924, and the publication by Sidney Smith of a document called « Verse Account of Nabonidus », that the principle of a co-regency between Nabonidus and Belshazzar was actually confirmed on the basis of the following passage 8:

« In the beginning of the third year, he [Nabonidus] entrusted the military camp to his first born son [Belshazzar]. He put under his command the army of all the lands. He let everything go [withdrawing from business] and entrusted the kingship to him and, as for himself, he took the path to distant regions. The military forces of Akkad taking the field with him, he set out towards the city Teima, in the midst of Amurru »

BM 38299, col 2, li 17-23

Thus, it is evident that Belshatsar exercised royal authority from the third year of Nabonidus, which probably corresponds to « the first year of Belshazzar the king of Babylon » mentioned in the Bible in Daniel 7:1. However, this last expression does not appear in any of the documents found until today. If « in documents dated to the period of the Teima stay, Belshazzar often appears attending to administrative matters which would normally be the king’s responsability » 9, the title by which he is appointed is invariably « mar šarri » — « son of the king » in the sense of crown prince. This explains why, on the evening of the capture of Babylon by the Medes and the Persians, Belshazzar could not offer to the prophet Daniel — who had revealed to him the exact interpretation of a mysterious expression appearing on a wall — nothing better than « the third place in the kingdom » (Daniel 5:29), the first two being occupied by his father and himself. This element supports all the more the historicity and the contemporaneity of the book of Daniel that the classical authors always ignored both the name and the particular status of the number two in Babylonia! But then, you will say, why did Daniel call Belshazzar «king » if the latter was not really king?

The discovery in 1979, in Tell Fekheriye in Syria, of a statue of a high dignitary, allows us to answer this question. The statue of Hadad-Yith’i has two inscriptions, one on the Assyrian front and the other on the Aramaic back — the language in which the biblical account of Belshazzar was written. The first inscription qualifies the man as «Governor of Gozân », while the second does not hesitate to present him as « King of Gozân.» Therefore, if it was logical that Belshazzar be qualified as «Crown Prince » on the official inscriptions of Babylon, locally, « it is quite in order for him to be called ‘king’ in unofficial documents such as the book of Daniel. He acted as king, even if he was not legally king, and the distinction would have been irrelevant and confusing in the story » 10. Here we find ourselves in the presence of a common practice at the time, but which was abandoned in the following centuries. Also unknown to the profane authors who recounted the history of Babylon, it attests that the editor of the book of Daniel could only be an eyewitness to the facts he relates.

Today, Belshazzar is a historical figure well authenticated by at least 38 archival texts 11 dating from the reign of his father Nabonidus and which underline the accuracy of the information coming from the Bible. Two other inscriptions (AMF 135 and YBC 3765), dated respectively from the end of the reign of Amel-Marduk and the beginning of the reign of Neriglissar — the two immediate successors of Nabuchodonosor II — also mention a « Belshazzar, the king’s chief officer » whose identification is uncertain, his affiliation not being specified. « There is, therefore, no registered proof (…) that the Belshazzar who was a chief officer of the king in the time of Neriglissar was the son of Nabonidus and hence the Biblical Belshazzar » 12. A remark that leads a contemporary researcher to make the hypothesis that « the name ‘Belteshazzar’, which is the form in which Daniel’s Babylonian name was written in the book [which bears his name], probably was derived from an original ‘Belshazzar’ (…). From this proposal to identify Belshazzar, the šaqu šarri of Amel-Marduk, with Bel(te)shazzar of the book of Daniel, it can be seen that Daniel probably occupied, albeit briefly, yet another (…) post in the Neo-Babylonian government that is not reported in the book [which bears his name] » 13. Whether this identification is confirmed or not, it testifies to the interest that the study of the book of Daniel continues to arouse, both historically and in the light of the prophecies it contains. Prophecies to which we would do well to be interested because many of them are realized in our time!

References

| 1 | Hérodote, « Historia », I, 191. |

| 2 | Xénophon, « Cyropaedia », VII, [5], 15, 29-30. |

| 3 | Clyde E. Fant, Mitchell Reddish, « Lost Treasures of the Bible: Understanding the Bible through Archaeological Artifacts in World Museums », 2008, p. 234. |

| 4 | William Henry Fox Talbot, « Assyrian Texts Translated », Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 19, 1861, p. 195. |

| 5 | Frauke Weiershauser, Jamie Novotny, « The Royal Inscriptions of Amel-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon », The Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Vol. 2, 2020, p. 163. |

| 6 | Albert Kirk Grayson, « Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles », 1975, pp. 106-108. |

| 7 | Theophilus G. Pinches, « Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archaeology », Vol. 7, 1882, p. 150. |

| 8 | Paul-Alain Beaulieu, « The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556-539 BC », 1989, p. 150. |

| 9 | Ibid., p. 155. |

| 10 | Alan Ralph Millard, « Treasures from Bible Times », 1985, p. 140. |

| 11 | Paul-Alain Beaulieu, « The Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon 556-539 BC », 1989, pp. 156-157 |

| 12 | Raymond Philip Dougherty, « Nabonidus and Belshazzar », 1929, p. 68. |

| 13 | William H. Shea, « Bel(te)shazzar meets Belshazzar », Andrews University Seminary Studies, 1988, Vol. 26, pp. 79-80. |