The Testimony of the Scriptures

Jesus was on his last evangelization tour when he was approached by Pharisees, members of the most influential Jewish sect of his time, who saw this as a favourable opportunity to make him look like an impostor and a false teacher. So, they « tried to trap him with this question: ‘Should a man be allowed to divorce his wife for just any reason?‘ » (Matthew 19:3, NLT). The question was all the more delicate in that it frequently gave rise to heated debates between rival religious factions, some of which, for example, went as far as allowing a man to divorce his wife simply because she had « burned or over-salted his dish » 1. Jesus’ response somewhat surprised his interlocutors: « Have you not read that He who made them from the beginning made them male and female, and said, ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh’? » (Matthew 19:4-5, RSV). Confused, the Pharisees tried to justify their reasoning by quoting an article from the Mosaic Law, but Jesus confused them with these words: « Because of the hardness of your hearts Moses allowed you to divorce your wives, but from the beginning it was not so » (Matthew 19:8, NAB).

This episode from the Gospels underlines how concerned Jesus was to bear witness to the truth. Far from imitating his interlocutors, who were accustomed to philosophizing about the possible applications of sacred texts, he naturally referred to the founding principles, basing his argument on two passages from Genesis (1:27; 2:24) and one from Deuteronomy (24:1), writings of which the « ancient Jewish tradition attributed the authorship (…) to Moses himself » 2, to confirm its adherence to the work left by the latter. As the account reveals, Jesus’ encouragement to return to the « beginning », to the true sources of history and religious thought, was particularly appropriate at a time when the critical mind of the Pharisees dominated his contemporaries. It is even more necessary today when our society is the scene of regular jousts between believers, faithfully attached to the biblical source of their faith, and skeptics, won by rationalist and often anti-religious philosophy which, in the last two centuries, led to the emergence of the documentary hypothesis and its naturalistic counterpart, the theory of evolution.

Focusing more specifically on analyzing textual sources, the documentary hypothesis popularized the idea, from the last quarter of the 19th century, that the Pentateuch, far from being the legacy of Moses, was nothing other than « the product of a long and complex literary evolution, specifically incorporating at least four major literary strands composed independently over several centuries and not combined in the present form until the time of Ezra (fifth century B.C.) » 3. One of the first arguments put forward concerned the different names in the book of Genesis of the God of Israel — Jehovah, God or the combination of the two — which would imply the existence of two separate “documents“, the first called J (for Jehovah and Judah) having been produced « probably (…) in the Jerusalem of the ninth-century BCE »; the second, baptized E (for Elohim), « focused on the religious sites in the Northern Kingdom », probably in « Samaria, the capital of Israel, in the eighth century BCE » 4.

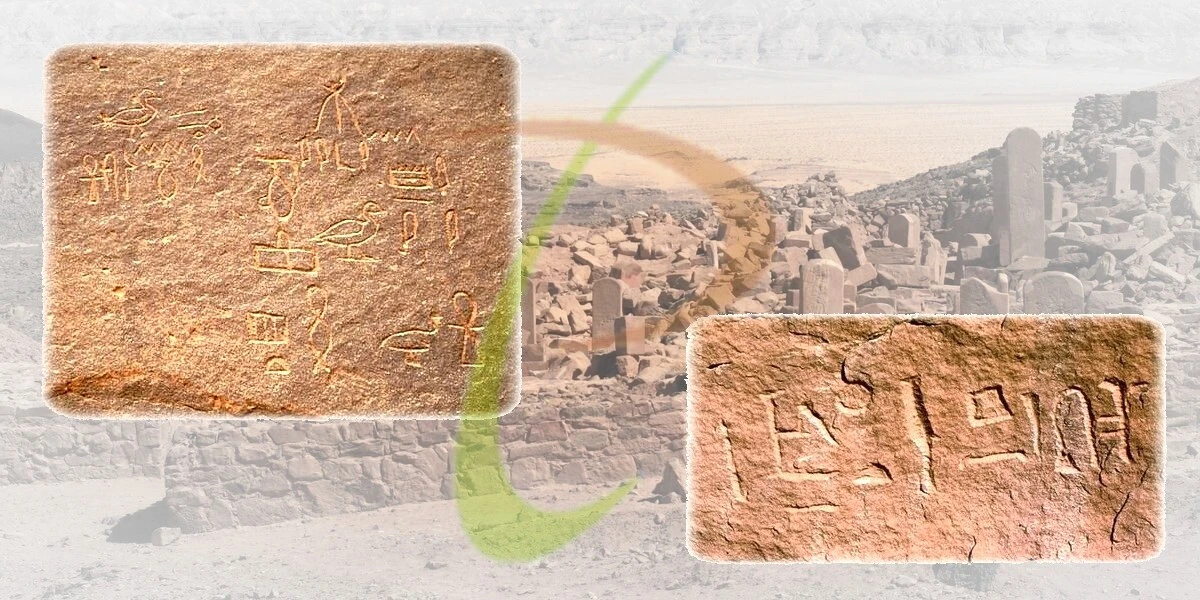

Here is how the biblical scholar Gleason Archer showed the weakness of this argument: « On the basis of comparative literature of the Ancient Near East, all of Israel’s neighbors followed the practice of referring to their high gods by at least two different names — or even three or four. In Egypt Osiris (…) was also referred to as Wennefer (He who is Good), Khent-amentiu (Foremost of the Westerners), and Neb-abdu (Lord of Abydos); and all four titles occur in the Ikhernofer Stela [BM 1204] in the Berlin Museum » 5. Egyptology further proved that Moses was well able to produce the documents attributed to him by tradition. « Writing in both hieroglyphic and hieratic characters was so widely prevalent in the Egypt of Moses’ day that it seems absolutely incredible that he would have committed none of his records to writing (as even the twentieth century critics contend) (…). At a time when even the unschooled Semitic slaves employed at the Egyptian turquoise mines in Serabit el-Khadim were incising their records on the walls of their tunnels, it is quite unreasonable to suppose that a leader of Moses’ background and education was too illiterate to commit a single word to writing » 6. Let us recall here that the mines of Serabit el-Khadim were located in Sinai on the road taken by the Israelites during their wanderings in the desert, and that the inscriptions discovered there are dated « from 1500 BCE at the very latest » 7. More than disturbing coincidences, they are evidences that nothing prevented Moses from composing the Pentateuch many centuries before the date advanced by his detractors.

The numerous tablets found in Nuzi, in the south-east of Nineveh in Iraq, also confirmed the historicity of the book of Genesis, bringing splits on several customs in vogue at the time of the patriarchs. Thus, « it was a custom at Nuzi for childless people to adopt a son to serve them as long as they lived and to bury and mourn for them when they died. In exchange for these services, the adopted son was designated as an heir. If, however, the adoptor should beget a son after the adoption, the adopted must yield to the real son the right to be the chief heir » (tablet H V 7) 8. This explains the promise that Jehovah made to Abraham that his servant Eliezer — whom he had probably adopted — would not be his heir (Genesis 15:2-4). Similarly, « the marriage contracts at Nuzi contained a provision obliging a childless wife to provide her husband with a handmaid who would bear children. This explains the action of Sarah in giving Hagar to Abraham (Genesis 16) and of Rachel in giving Bilhah to Jacob (Genesis 30:1-3). (…) The offspring of the handmaid could not be driven out, which shows that there was a legal basis for Abraham’s apprehension over the expulsion of Hagar and her child (Genesis 21:11) » (tablet H V 67) 9. Several tablets found in Nuzi also corroborate the account recorded in Genesis 25:33 of Esau’s sale of his birthright. One of them (N 204) relates that « a man by the name of Tupkitilla transferred his inheritance rights (…) to his brother Kurpazah in exchange for three sheep (…). But just as Kurpazah exploited Tupkitilla’s hunger, so did Jacob take advantage of the famished Esau » 10. Another tablet (G 51) makes it possible to draw an interesting parallel between the story of Jacob’s tense relations with his father-in-law Laban (Genesis 29-31), and that of a man named « Nashwi and his adopted son called Wullu (…). Nashwi bestows his daughter upon Wullu, even as Laban promised a daughter to Jacob when he received him into his household. When Nashwi dies, Wullu is to be the heir. However if Nashwi begets a son, Wullu must share the inheritance with that son, and only the latter shall take Nashwi’s [domestic] gods (…) [and, therefore,] the leadership of the family. Since Laban had sons of his own when Jacob departed for Canaan, they alone had the right to have their father’s gods, [so] the theft of the teraphim by Rachel (…) was a serious offense » 11. To what conclusion should the mention of all these archaeological documents lead us?

Perhaps to that expressed by the Hebrew scholar Harold Rowley: « In all of these cases we have customs which do not recur in the Old Testament in later periods, and which therefore are not likely to reflect contemporary society in the age when the [textes génésiaques] were written (…). Their accurate reflection of social conditions (…) in some parts of the Mesopotamia from which the patriarchs are said to have come, many centuries before the present documents were composed, is striking (…). Ít is now becoming increasingly clear that the traditions of the Patriarchal Age, preserved in the book of Genesis, reflect with remarkable accuracy the actual conditions (…) of the period between 1800 and 1500 B.C. » 12. Therefore, it seems obvious that the « remarkable accuracy » of these customs and traditions would have been forgotten if the Pentateuch had been written long after that late date. Especially as the seniority of its writing is confirmed by many expressions which also testify in favor of a unique original work.

« When the writer has occasion to mention the titles of any official », explains the biblical scholar John Garrow Duncan, « he employs the correct title in use and exactly as it was used at the period referred to, and, where there is no Hebrew equivalent, he simply adopts the the Egyptian word and transliterates it into Hebrew. (…) So when he makes his brethren speak of Joseph as ‘the Man’ [Genesis 42-43], the writer employs a title then in use for the vizier or king’s double. As vizier Joseph was “the Man”, the foremost man in the kingdom. Again, when he speaks of Aaron as Moses’ “mouth” or spokesman [Exodus 4:16], he is employing an Egyptian official title in regular use. During the time of the Hebrew sojourn [in Egypt], (…) there was a body of high officials at court who acted as intermediaries between Pharaoh and his people. The “Mouth” was the title of the highest of these mediators, and he was generally the heir to the throne. In his use of ‘Pharaoh’, too, as a title, the writer is historically accurate. In fact, nothing more convincingly proves the intimate knowledge of things Egyptian in the Old Testament, (…) than the use of this word ‘Pharaoh’ at different periods » 13. It is true that this expression is particularly emblematic of the ancient disagreements over the historicity of both the Pentateuch and Moses as its editor. Many exegetes have denied both on the basis that the personal name of the Egyptian monarch is never mentioned in the early books of the Bible. Nevertheless, the defenders of the inspired text recalled that the expression « per-aa », literally « big house », was rising, in reference to the royal palace, « to the Old Empire, but as an epithet for the monarch, it only appears in the eighteenth dynasty (…) Until the tenth century, the term “Pharaoh” was alone, without a personal name juxtaposed. (…) In fact, the use of ‘Pharaoh’ in Genesis and Exodus is consistent with Egyptian practice from the 15th to the 10th century [BCE] » 14.

Now, if the « conformity to Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian usage turns out to be strong evidence of a Mosaic date of composition » 15, both dates are still validated by the expression « all the land of Egypt » who — except for one mention in the book of Jeremiah — appears only in Genesis and Exodus, in connection with the accounts relating to Joseph and the devastating plagues. « The fact (…) that Egypt was ever called by a name of dual formation, leads us to conclude that the name ‘Misrayim’ — ‘the two lands’ — was an original creation of the Hebrews from the Egyptian ‘tawy’ (…) — ‘twinland’ —, [name that] always existed, and had always remained the official name fot Egypt » 16. By using the word « misrayim », the author of the Pentateuch was referring to this « twinland » shared between Lower and Upper Egypt, fully aware that the events he described in Genesis and Exodus had occurred at a time when Pharaoh’s power still extended to « all the land of Egypt », that is to say over all the « two lands ». However, this situation no longer existed during the first millennium before our era, which invalidates the composition of the two accounts concerned « in their present form » in this late era — as dogmatically claimed by the proponents of the documentary hypothesis. This led one of them to admit « that the person who either wrote (…) the Joseph sagas had an exceedingly intimate knowledge of Egyptian life, literature, and culture, particularly in respect to the Egyptian court, and in fact, [he] may even have lived in Egypt for a time » 17. Why, therefore, do not recognize that this « person » corresponds, on all the enumerated points, to the biblical Moses, « since he appears to have possessed all the qualities and training necessary to fulfill the role of author » 18?

« As we have seen, in the earlier stages of the [documentary hypothesis] history grave doubts were cast on much of the historical character of the Pentateuch, in particular on the Genesis narratives. This situation has changed, owing in great part to the results of archeological work. The ruins themselves and, above all, the literature of other ancient peoples have provided an authentic background (…) a sufficient historical basis to support the weight of the credal interpretation that is their principal object »

Christopher T. BEGG & Eugene H. MALY 19

However, the testimony of archaeology, although very precious, could not equal that of the greatest defender of the Holy Scriptures that was Jesus of Nazareth. « Did not Moses give you the Law? » (John 7:19, RSV), had he thrown to Jews gathered in the temple of Jerusalem. For him, the historicity of Moses was beyond doubt and the authority of the Scriptures attributed to the prophet was indisputable. As we saw in the introduction, Jesus supported the Genesis story of the foundation of the human family. That is, he did the same for the historicity of Adam and Eve, and for the murder of their son Abel, to which he alluded in Matthew 23:35. He likewise authenticated the Flood in « the days of Noah » and the destruction of the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah (Matthew 10:15; 23:37-38). But these facts, detailed by Moses from documents probably passed down from generation to generation, are still too often presented as myths because their critics are unable to integrate an essential data into their reasoning — a data whose absence inevitably leads to false conclusions. What is it about?

« Are you not in error because you do not know the Scriptures or the power of God? » (Mark 12:24, NIV). This was the answer Jesus gave to the religious leaders who ventured to join him. It invites us to admit that the proper understanding of the Sacred Scriptures depends on the acceptance of that « power of God » which was manifested, among other things, through the miracles that Moses and Jesus performed. Now a miracle, by definition, is a work or a phenomenon that exceeds human understanding. This has the merit of clearly posing the crux of the problem at the origin of the secular jousts between skeptics and believers. For the former, miracles are nothing more than nonsense, since their spiritual dimension goes beyond the field of experimentation of Science — which thus reveals one of its most damaging limits. Those who are sincere in their conviction resemble the apostle Thomas, to whom Jesus made this relevant remark: « Because you have seen me, have you believed? Happy are those who have not seen and yet believe » (John 20:29, NWT). For people of faith now, miracles are one of the manifestations of the action of the Holy Spirit or God’s working force, an « invisible reality » that can take various forms in the daily life of each one. Like Jesus, true believers demonstrate an unconditional attachment to the Holy Scriptures, fully convinced that they contain the truth inspired by Jehovah God. In a prayer to him, Jesus recognized the authority of the whole inspired text when he told him: « Your word is truth » (John 17:17, WEB). Would that also be the view that you and I share?

References

| 1 | Talmud de Babylone, Gittin 90a. |

| 2 |

Joseph Jacobs, « Pentateuch », The Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol. 9, 1905, p. 589. |

| 3 |

Daniel I. Block, « Pentateuch », Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 2003, p. 2427. |

| 4 |

Mark Elliott, Paul V. M. Flesher, « Introduction to the Old Testament and its Character as Historical Evidence », The Old Testament in Archaeology and History, 2018, pp. 66-67. |

| 5 |

Gleason L. Archer Jr, « Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties », 1982, pp. 58-59. |

| 6 |

Gleason L. Archer Jr, « A Survey of Old Testament Introduction », 1964, p. 109. |

| 7 |

Ibid., p. 158. |

| 8 |

Cyrus H. Gordon, « Biblical Customs and the Nuzu Tablets », The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 3(1), 1940, p. 2. |

| 9 |

Jack Finegan, « Light from the Ancient Past, the Archeological Background of the Hebrew-Christian Religion », 1959, p. 54. |

| 10 |

Cyrus H. Gordon, « Biblical Customs and the Nuzu Tablets », The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 3(1), 1940, p. 5. |

| 11 |

Jack Finegan, « Light from the Ancient Past, the Archeological Background of the Hebrew-Christian Religion », 1959, pp. 54-55. |

| 12 |

Harold H. Rowley, « Recent Discovery and the Patriarchal Age », Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Vol. 32, 1949, pp. 76, 79. |

| 13 |

John Garrow Duncan, « New Light on Hebrew Origins », 1936, p. 174. |

| 14 |

James K. Hoffmeier, « Israel in Egypt, the Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition », 1997, pp. 87-88. |

| 15 |

Gleason L. Archer Jr, « A Survey of Old Testament Introduction », 1964, p. 105. |

| 16 |

Abraham S. Yahuda, « The Accuracy of the Bible », 1935, p. 21. |

| 17 |

Alan R. Schulman, « On the Egyptian Name of Joseph : A New Approach », Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, Bd. 2, 1975, p. 236. |

| 18 |

Norman Geisler, Joseph M. Holden, « The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible, Discoveries that confirm the Reliability of Scripture », 2013, p. 59. |

| 19 |

Christopher T. Begg, Eugene H. Maly, « Pentateuchal Studies », New Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 11, 2003, p. 94. |